Lamorna Homes

Flagstaff Cottage

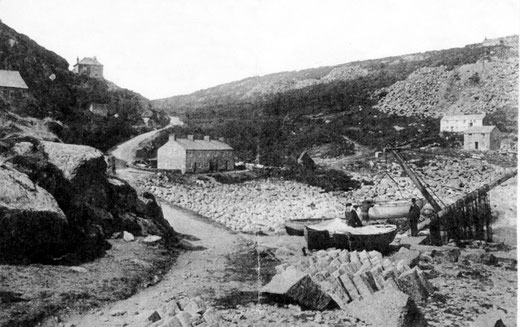

Granite Quarries at Lamorna - an 1873 coloured etching, showing Flagstaff Cottage on the right

As far as I know, Flagstaff Cottage was built as the Harbour Master's cottage about 1840. I think it was built at the same time as the quay was built and also the hotel, which was the residence of the Quarry Manager and also contained a chapel. These were built by the Boskenna Estate, and the quarry being served was to the west of the Cove, and not the large one that dominates the Cove today. At some stage, the quarry was found to have poor quality granite and, after a period it was closed.

When first built, and, indeed, when my grandfather arrived in 1902, Flagstaff Cottage was a simple square structure, with two rooms and a hallway on the first floor and two rooms upstairs. This can be seen in some of the early paintings and etchings. There was probably a lean-to kitchen at the back.

I think that when it was first built, the building by the stream was built to house a pony and trap and, when my grandfather moved in, he used it as his studio.

Prior to my grandfather moving in, Flagstaff Cottage was rented by an author - Charles Marriott [(1869-1957)see book,Charles Marriott Genevra (1904)]. Colonel Paynter, who owned Boskenna Estate, did not at that time sell properties and believed only in renting. It was not until about 1930 that my grandfather was able to buy the house and the studio. He continued to rent the land by the stream between the house and the studio and developed this as a flower and vegetable garden.

When my mother was about ten, it was decided that more room was needed for her and sister Joan and so, in about 1915, the family decamped for a period to Trevider Farm, while the L shaped addition was added to the west side against the cliff. This greatly changed the cottage to really become a house. The addition included a front and back kitchen with an entrance to the back kitchen through a stable door. Selina Ladner had been hired as a housekeeper and cook, and the kitchen area was her domain, with a Cornish slab in the front kitchen and a clothes boiler in the back kitchen. Mary Ladner, Selina's sisiter would come to do the washing in this facility once a week. on the top floor, there were now two bedrooms for Joan and Mornie and a bathroom in between.

I am not certain of the dates but various outbuildings were erected in the first half of the twentieth century. Above the house and up some rather steep granite steps was a black painted wooden hut which, for a time, served as the home of a fisherman, John Jeffery. He was befriended by my grandfather and no doubt provided the family with fresh fish.

My grandmother had a small wooden shop built beside the road and on the left side of the driveway. This was to sell handicrafts, including some hand drawn postcards of Lamorna places by my grandfather. To prepare materials for the handicraft shop and also for storage, a cement block building was built above the house to the northwest.

Over the years, these outbuildings have had many different uses.Old John Jeffery must have moved on. I know his son Ben became an active fisherman in Mousehole. On being demobbed after the War, my father totally re-built the black hut out of cement blocks - a major task as all these had to be hand carried up the steps. Later in 1963, when he died, it became a rental property and various people stayed in it. In about 1990, it was extended to include a small separate bedroom and a bathroom.

My grandmother died in 1944 and we moved to Lamorna. By that time, the two bedrooms of the original house had been converted to provide a much larger bedroom with windows looking out to sea. When we moved in, my parents moved to one of the back bedrooms and I to the other. On my grandmother's death, the handicraft shop stopped trading and eventually fell apart and was destroyed.

In about 1950, my parents decided it was time to pension off Selina and to modernise the house. During my grandfather's earlier time, the original downstairs had been divided into a small sitting room and a formal dining room but it was decided to break down the wall between the two and make one larger sitting room. Selina's front kitchen, which had included a Cornish slab, was changed to a dining room and the back kitchen became the main kitchen with an Aga, and a refrigerator.

During my grandfather's last year, it was decided to build a studio above the garage that had been built as part of the much earlier extension. The idea was that my grandfather could go from his bedroom to this studio, but it was never used as such and since then has served as a sort of retail outlet for my grandfather's and other family art. My grandfather had incidentally had a much larger studio built further up the valley once he had established his reputation, but it was a bit of a walk and never used to the extent of the studio by the stream. On my grandfather's death, this was inherited by my Aunt Joan who was living in Australia and she sold the property. It has been much modified and enlarged and is now owned by a retired commercial artist, John Beresford.

My mother had for many years talked about converting the studio by the stream as a residence that she could let. Plans were made but this work did not start until her death in 1990, and it is now a comfortable little renting property that houses two or three people. Another generation change following my mother's death was to build a conservatory on the seaward side of the living room. Much earlier my grandmother had had a small bay window, but the conservatory has replaced that with a spacious area that enjoys much use including on occasions the annual champagne toast of The Lamorna Society.

Adam Kerr

Postcard of Lamorna c 1922. On the left is the lime kiln and above this the Magazine. At the top is Flagstaff Cottage. Donated by David Evans

Menwinnion

In 1912, Frank Heath purchased ten acres of land at the top of the Lamorna Valley from Col. Paynter, one of local large landowners, on which to build a house.The architect was a Mr Stacey, who lived locally, and the house was built by the Matthews family from Newshop, St Buryan. The land, when bought, was just a scrubland field enclosed by a stone wall.As was then common, granite from which the house was built, was hand drilled out of the ground on the site and then split and shaped into the sizes of blocks required. The house took a year to build, cost £1,000 and was christened 'Menwinnion'- perhaps taking its name from the Cornish- men (meaning stone) and gwynn (meaning white or speckled).

The house consisted on the ground floor of the hall, morning room,dining room,kitchen, scullery and cloakroom. Upstairs were 5 bedrooms, a bathroom and 2 attic rooms. In the garden, Cornish stone walls were constructed and fuchsia and escallonia hedges planted as windbreaks. From the holes made by the excavation of granite, several 'courts' were created and named 'Lavender', 'May' and 'Wood'; below these courts a pond was dug out. The bottom half of the garden was planted with Monterey pine and it was here that Frank Heath built his first studio. He subsequently built another adjoining the main house.

The years of the Great War cannot have been easy for Frank Heath's wife, Jessica at 'Menwinnion'. Frank had enlisted into the 2nd Sportman's Battalion in 1915. Food was short; vegetables and fruit were grown in the garden, and eggs, butter and meat were available from the surrounding farms; in addition food parcels were sent from Jessica's parents from Penzance. The water for the house had to be pumped up by hand from the well in the courts.

Several other local artists used to visit and enjoy the hospitality at 'Menwinnion'. These included Alfred Munnings and his first wife, Florence, who became great friends, Stanhope Forbes (Frank and Stanhope used to play music together - on their cello and violin respectively), Laura and Harold Knight (Laura had a studio at the bottom of Heath's garden) and 'Seal' Weatherby.

Frank featured both the interior and exterior of his property in his paintings. For instance, shortly after the house was completed, he exhibited The Morning Room at Menwinnion at the Royal Academy in 1914. This featured Jessica playing the violin, whilst later works featured his children in different rooms in the house. Accordingly, The Little Maid (RA, 1923) shows Nancy in the hall, whilst The Butterfly, (RA, 1928) shows Gabriel in the bathroom. The Lily Border, which was featured at the Newlyn Art Gallery in 1916, shows Jessica in what was a distinctive section of the garden, whilst a large painting The Fairy Story, shows all four children by the pond at the bottom.

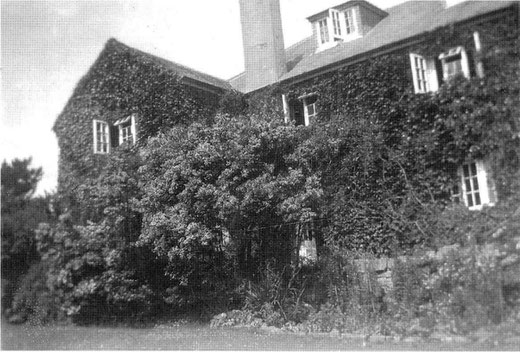

In the 1930s Frank heath's health began to fail, due to continuing chest problems and he died in a London hospital in 1936 aged 63. Shortly afterwards, Jessica decided to sell 'Menwinnion', now enveloped in ivy, and moved up to Dorset. The house was bought by John and Nicky Williams, the brothers of Colonel James Howard Williams, known as 'Elephant Bill' from his exploits in Burma during the 2nd World War. The brothers had been brought up in St just. Before the War, 'Elephant Bill' was employed by the Bombay Trading Company, who used elephants to transport teak. Using his rapport and expertise with elephants, in 1942, when the Japanese invaded Burma, he joined the Special Forces Unit that specialised in guerrilla warfare, with the Elephant Company helping with the building of bridges and the ferrying of weapons and suuplies for Gen.Slim's 14th Army.

After the War, 'Elephant Bill' returned to West Cornwall and, after an unsuccessful time as a market gardener and a farmer, he lived at 'Menwinnion'. Clearly, he had always had a soft spot for Lamorna., as he called his daughter that name. To his utter amazement and amusement, his books recording his time in Burma- Elephant Bill (1950) and Bandola (1954) were enormous successes. The first proved a record-breaking best seller, and he was able to sell the film rights for both books, being flown out to Ceylon and then Siam to locate suitable locations for filming. He also found himself in demand as a lecturer around the country. His portrait, painted, at this time in his library at 'Menwinnion' by Midge Bruford, is now owned by Penlee House. In 1956, he wrote the Foreward for the second addition of Crosbie Garstin's The Owl House, in which he said that his own taste for adventure had been sparked by those of Garstin, whom he described as 'my first, and only, boyhood hero'. He died in 1958 in West Cornwall hospital following an operation for appendicitis at the comparatively early age of 61. In 1963, his widow, Susan Williams, wrote an account of their life together called The Footprints of Elephant Bill, in which she commented (at p221), 'Our final home together, 'Menwinnion', just above Lamorna Cove, did perhaps fulfill the dream that Jim had always had. For the first time in our lives, there was a beautiful garden always made for us. Just beyond lay his favourite cliffs, where he would sit and write or paint; I don't think anyone could have been happier'.

After 'Elephant Bills' death, 'Menwinnion' was sold and became a very comfortable Country House Hotel. The ivy was removed and the large garden continued to be well kept. Then in the early 1980s, it was sold again to become a Country House are Home, which it remains today, although now so greatly extended that the original ambiance is lost. A plaque was erected in the entrance to the Home in 2012 to celebrate the first 100 years of the house.

Hugh Bedford and David Tovey

Trewoofe House

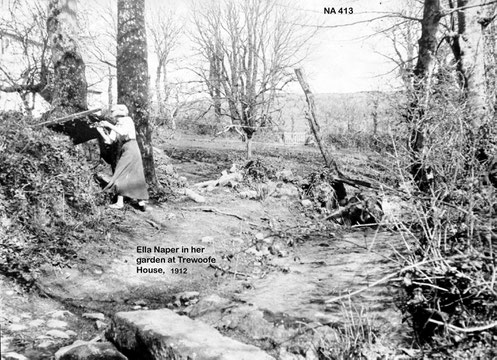

Prior to moving to Lamorna in 1912, the painter, Charles Napier, and his wife, Ella, a jeweller and potter were living in Looe. Quite how they selected Lamorna as the place, for their new home is unclear, but they probably heard of its attractions through friends in the art world. In any event, they bought off John Richards, of St Buryan, three meadows, of about two acres, for £250, with help from charlie's family. These were just behind 'Trewoofe Farm' and the leat for 'Clapper Mill' ran through the land. Charlie designed the house- some of the seven years spent at the Royal Academy School being spent on architecture. He also later designed 'Duncans'. The house, built in granite, was very small, really a cottage; two bedrooms upstairs, bathroom, kitchen,with a coal fired Rayburn, and sitting room downstairs. As well, there was a large open plan room of one storey, which was part of Ella's workroom and, until after the war, Charlie's studio. This was built of some kind of block-work, with a corrugated roof. The existing studio was built at right angles to the open plan room when charlie returned from the war. The water was from large tanks collecting rain water and remained like that until the 'mains' came to Trewoofe in 1960s. I don't know when electricity was installed, but I believe that Charlie did the wiring himself! They did not garden all the land, but they made flower beds around the house, using granite from the first Cornish hedge, which was demolished. They grew their own vegetables, with Ella even selling garlic to Harrods during the Second World War! At a later date, Charlie kept bees, and became absorbed with the leat, building a sluice gate which created a large pond deep enough for trout at the far end. John Lamorna Birch's painting Ella's Garden (1938) shows the pond. I have made this into a bog garden,as it was completely overgrown when I came to live here. They also planted an orchard. THe rest of the land was let out between the wars for early flower growing. Two ladies, Dod and Palmer, worked it for a while, growing violets, anemones and daffodils. When I took over in 1975, Wellee Clemens, a nearby farmer was growing vegetables and daffodils.

Charlie died in 1968 and Emma in 1972, when I inherited Trewoofe. I could not manage to come and live here until the summer of 1975. I had four school-aged daughters, so it was necessary to make some changes. Ella thought that I would be able to make bedrooms above the single story room but I knew I couldn't as it was falling down. I also had the electricity disconnected as it was unsafe. I had to have an architect draw up plans and apply for planning permission, although I knew the layout I wanted.

There are now six bedrooms and two bathrooms upstairs. I moved the kitchen to the open plan room- it is now a large kitchen and dining room with an oil-fired Rayburn. I also added a single storey sitting room at right-angles to the kitchen, as the original sitting room was not large enough for all of us and the girls' friends. The studio has been much in use over the years, sadly not for its original purpose as none of us have Ella and Charlie's artistic talents. I did hear that during the twenties and thirties it was a popular place for courting.

One of the first things I did was to have a drive made up to the front door from the lane. This involved having a bridge built over the leat strong enough for cars. While all this was going on, we had a winter holiday let at 'Oakhill'.

The farm was sold by the Trewerns in the early seventies. Over time, all the barns were converted into holiday lets and it was then that the GPO decided to name the properties individually and we became 'Trewoofe House'.

I have always loved gardening, so I took back the meadows straight away to make a vegetable garden. I planted espalier and cordon fruit trees. The first shrub bed was planted in April 1976; now there are many mature trees and shrubs and there is always something in bloom.

Maryella Pigott

Vellensagia

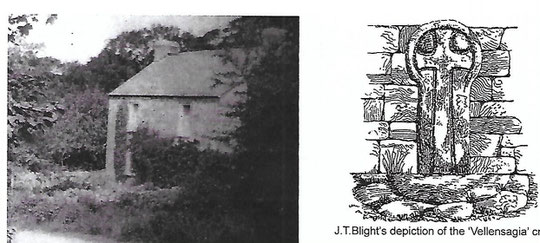

Vellensagia in the 1930s

Vellensagia, which is situated on the road from the Lamorna Pottery to St Buryan, might not be considered a Lamorna property today, but, in the years 1906-1912, when it was occupied by Cecily and Alfred Sidgwick, it played a pivotal role in the life of the Lamorna community. It also featured in Cecily's 1923 novel None-Go-By, as the cottage of that name.

Member, Frank Ruhrmund, in what must have been one of his earliest pieces- an article in the Cornish Magazine in May 1964, entitled The Valley of Blood - pondered over the meaning of Veelensagia. The populist interpretation was that 'vellen' could mean 'valley' and that 'sagia' had some connection with sanguine, and that, accordingly, it referred to the conflict in c.936 between King Athelstan and the Cornish Rebels, aided by a group of red-haired Danes, which had resulted in the nearby Lamorna stream being red with blood for several days. However he felt that it was more likely that the name was related to the ancient craft of fulling, as there were at one time three tucking mills on the Lamorna stream. In this case, vellen would be related to 'Melyn', which means a mill, whilst sagia would be related to the Welsh word 'sagio', which means crushing.

Prior to moving to West Penwith, Cecily and Alfred had been living in Surbiton, Surrey. She had enjoyed some success as a novelist, initially under the pseudonym Mrs Andrew Dean, but Alfred's career as a philosopher had ground to a halt and he earned very little from his learned tomes and articles for 'Mind'. Cecily commented, 'For a long time we had been living on the edge of our income, and edges are uncomfortable'. They also wanted to get away from the demands of relatives and were attracted by Cornwall's climate having spent some time in Falmouth. in a piece, As Easy as Anything, Cecily commented,

'I have always hankered after the Simple Life, and had my own ideas

about it. Most people, if you can judge by their descriptions, seem to

think that you are not leading it unless you give up the comforts to which

you are used. My idea... was to give up the discomforts, such as high

rent and rates, big coal and gas bills, [and] expensive servants'.

Having tested out successfully the concept of 'the simple life' in some of the cottages let out by Edith Ellis, wife of Havelock Ellis, in Carbis Bay, they were recommended to Lamorna by writer, Charles Marriott, whom they had met at dinner at the Ellis' home. Marriott of course had lived in Lamorna at Flagstaff Cottage in 1901-2. Their London acquaintances thought their projected move was madness and a well-known literary critic told Cecily that she was making a great mistake, 'Cornwall had been overdone. Cornwall was banal. As a setting for a novel, it was unusable...You'll have to use the dialect, and the dialect will pin you down'. However, they were not put off and on a windy day in March 1906, they left the comforts and bustle of suburban London, and, on a fine, warm spring afternoon, first set foot in their isolated and very basic new home.

In her novel, Cecily renamed 'Vellensagia' as 'None-Go-By', as what they had been hoping for was peace and quiet, a place where no-one came near; however, what they found was a place where no-one went by, because they all dropped in! They appear to have first met local artists at the St Buryan Races, after which Alfred had invited them back to their new home not appreciating that they had neither space nor the provisions to entertain them. However with the help of the wives of the Rector and a local farmer, it was possible to provide a measure of sustenance to the crowd that descended on the cottage, and the artists were sufficiently impressed by the good humour shown by Cecily that they soon dropped in to make further acquaintance and to extend invitations to their houses. Cecily commented,

'Before long, we easily made friends amongst the artists, although we did not paint ourselves. Our relations with them were harmonious, and in some cases became intimate. Several of them lived in beautiful houses and entertained hospitably; others had a happy- go- lucky menage and asked you as they could. They were all generous by tradition and temperament, and although they worked hard, none of them were recluses. We said we were but, like my relations, they seemed unable to believe it. That began to walk out from [Lamorna] on Sunday afternoons and to have tea in our garden. When I was not too much afraid of [my maid] Emma, I kept them to supper'

Accordingly, it seems that in years leading up to the formation of the art colony in Lamorna 1912,artists from Newlyn frequently walked out to Lamorna on Sundays to have lunch with the Birches, and then sauntered up to the Sidgwicks for tea and, occasionally, supper.

Until very recently, despite being damaged in a fire in May 1962, which claimed the lives of the two elderly ladies then living there, the front of Vellensagia did not look vastly different to how it looked in the Sidgwick's time. It is a solid granite cottage with thick walls and two principal rooms on each floor. Accordingly, the windows on either side of the front door have other windows directly above them. In the Sidgwick's time, it had no porch and was approached from the front gate by a straight brick path, which then, by the front door, turned right angles in each direction, so that access could be gained around each side of the property. The front garden was bounded by a low stone wall, which appears to have continued around the whole extensive curtilage of the garden, albeit this is now completely overgrown by ivy and other vegetation. Up against the road-side of the wall, close to the front gate, was an ancient and much worn Latin cross, which stood on a circular base. However, this was later moved further up the road by the ladies who perished in the fire. Indeed, some locals took the view that the fire was retribution for this act.

When the Sidgwicks rented the property off Colonel Paynter, water was laid on but it had no bathroom (so they had baths in their bedrooms) and the toilet was in the garden in an outhouse. The cottage was very small, with just one tiny spare bedroom, but this was considered a boon, as it would deter visitors. The fact that a bat was in residence also, caused some commotion when the first guest did attempt to sleep there. The dining room was small, as well, with teapot brown tiles around the grate of the fire. However the property had a coach house and a barn. Cecily had envisaged using the barn as a lumber room, but Alfred commandeered both properties for the wood and other junk that he hoarded. His exasperated wife commented,

'Our friends always offer [Alfred] debris of an imperishable nature that would otherwise be thrown into a dustbin, and he accepts it all, explaining to me that you never know what you may want. Before we came to Cornwall, I tried to persuade him to throw his old hoards away and begin new ones. I assured him that even in Cornwall, he might find rusty hinges, old nails, bits of leaden pipes, three legged chairs, broken door handles, and such like; but he would not be persuaded. Nor would he leave a foot of wood behind'.

Wood was another of Alfred's passions and he always over-ordered when his carpentry skills were in demand. The state of his workshop was always so disgusting that is was christened by Cecily as his 'Mukden' - Mukden having been a town much in the news during the Russian-Japanese War of 1904. Whilst the terms 'coach house' and 'barn' connote buildings of some size, the existing outhouse buildings at the property are quite small.

There was quite a bit of land with the cottage, and this may have been one of the principal attractions for Cecily. This had been divided into nine different areas on various levels, each part surrounded by an old granite wall.

'Some of the the walls seemed to be of great age and were densely overgrown by ferns, grass, ivy, stonecrop, and penny wort; others were bare and draughty, and several of the rough stone steps leading from one enclosure to another were falling to pieces'

Cecily does not offer any explanation for the various enclosures, seemingly accepting that they were part of a previous landscaping plan. However, in his article on the property, Frank Ruhrmund indicated that there were suggestions that a small chapel might have existed on the site. He assumed that this idea had arisen because of the cross by the property, but it was felt that this was a boundary marker, as there were a number of others in the area. It was more likely that in his view that some of the walls were the remains of a seventeenth century cow house.

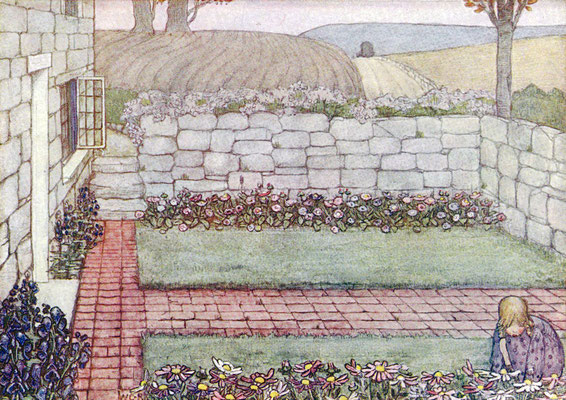

What has not been appreciated previously is that a number of illustrations in Cecily's book The Children's Book of Gardening, which she published in 1909 jointly with Colonel Paynter's wife, Ethel Nina Paynter, are of the garden at Vellensagia. These delightful illustrations were done by Winifred Cayley Robinson (1861-1936), the wife of the better known artist Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862-1927). They too had previously rented cottages off Edith Ellis and met Charles Merriott at the Ellis' home, whilst the children featured in the illustrations are likely to be their daughter, Barbara,aged 8, Elizabeth 'Mornie' Birch, then aged 4, for the Cayley Robinsons also became close friends of the Birches, and Betty Paynter, aged 2.

Cecily decided that the long narrow border that reached from one end of the garden to the coach house should be full of hardy perennials and that

'the two wide oblong beds on either side of the flagged path should be gay all summer with rows of pom-pom dahlias, African marigolds, Aster Sinensis and snapdragons. They should grow in straight rows face to face and be a riot of colour for months: and all the highbrowish gardeners would despise me because I grow common flowers in common rows'.

The Winifred Cayley Robinson illustrations used for the front and back covers of this Issue [Flagstaff 38] are likely to feature these beds. Cecily indicated that Alfred had never shown any interest before in gardening, but suddenly became quite enthusiastic. However, having selected the best areas herself for a vegetable patch and flower borders, she fobbed him off with a jungle and a marshy piece. Nevertheless, Alfred was not put out and set out to clear the jungle and create a rock garden, and then managed to drain water off the nearby stream, which ran adjacent to the property, to convert the marshy bit into a pond. A section of gunneras and some bamboo now reveal where his pond is likely to have been, and it may well have featured in Winifred Cayley Robinson's illustration, Irises.

As contrary to her literary agent's predictions, Cecily found a ready market for her Cornish based novels and began to be very successful. She could afford, in 1912, to buy land in the Trewoofe area and build Trewoofe Orchard. It does not appear as if Vellensagia proved attractive to other artists or writers once land nearer the Cove became available for purchase, and it was eventually sold off by Colonel Paynter in 1919. After the fateful fire in 1962, the back of Vellensagia was transformed by the incorporation of a glazed open staircase, designed by the young John Miller. The current owners are now in the process of significant renovations and extensions.

David Tovey

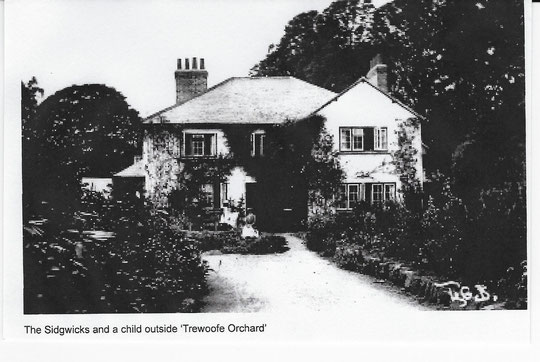

Trewoofe Orchard

The first home in Lamorna of the writers, Alfred and Cecily Sidgwick was Vellensagia, from 1906. However by 1912 Cecily's novels were proving so successful that they could afford to buy some two acres of land off Colonel Paynter in the Treewoofe area of the valley and erect thereon a new purpose-designed four bedroomed house, which they called Trewoofe Orchard. As this was the setting for the second half of Cecily's novel, Storms and Teacups (1931), which like her novel None-Gone-By, features Alfred and herself as Thomas and Mary Clarendon, she tells us much about the house, its layout and its decor, the garden, through which the Lamorna stream ran, rather too freely on occasions, and the access driveway, which required visitors to negotiate a ford. Furthermore she also makes reference to her discussions with her architect in her short story, The house Sensible, which was included in her 1913 collection Mr Sheringham and Others.

One of her principal concerns in the design process was the kitchen. In commenting upon the houses built by the previous generation, she exclaimed,

Look at their dark, damp basement kitchens; look at their wicked staircases; consider their attics! The wonder is that women can be found to toil in them. The wonder is that those who do have nerves and tempters left'.

She was equally dismissive of the newly built homes in suburbia, where

'The jerry builder thinks any God-forsaken corner will do for serving wenches to spend sixteen hours a day in, and he puts them a window half a yard from a blank stucco wall'.

Her kitchen was to be light and airy and have a view. On presenting his plans, the architect made clear his priorities, stating,

'Here are wall spaces for every bit of your furniture. Here are two feet granite walls, so that neither heat nor cold can trouble you or sounds annoy; here is your kitchen as pleasant as your dining room; here are hot and cold taps - here - here - there (no carrying of water in my houses); here are your cupboards; your tiled hearths and fenders, your tiled sinks, your wide easy stairs, and your big casement windows that let in the sun'.

Cecily was rather disappointed that she could not have the roof of her dreams, with 'drooping red eaves that hang like brows over the ground floor rooms', and that there were no quaint, pointed gables, with little windows high up in them like eyes', but these did not fit with The House Sensible.

Trewoofe Orchard was not that large, being, in effect, a thirty feet square box, albeit a gable frontage has been added to one side. There was no porch initially and, on entering the hall, which had a coat cupboard that ended under the stairs, Albert's study, which was lined with books, on the left. On the right was the dining room, which had a large window looking down the drive, whilst, at the back on that side, was the drawing room, with a window seat that overlooked a trout pond that Alfred created. The kitchen, with scullery and a coal house, was behind the study, and again had fine views over the pond and the back of the garden. There were four bedrooms in all, but Cecily and Alfred had separate ones, with a connecting door. These were above the main reception rooms. There was just one bathroom.

Internally, none of the rooms had any particular features of distinction, albeit a large granite lintel was placed over the range. Cecily repeatedly indicated that Alfred and herself has no artistic sensibilities, and descriptions of their home tend to referv to it as being pleasant and simple. In the novel, it is the smallest of the fur bedrooms that she describes in some detail, so as to give some indication of her taste. This had its own wash basin and was a cosy little room, as it was warmed by the kitchen chimney and study chimney.

'The walls...are a warm.pale yellow like the petals of primrose, the curtains, carpet and silk eiderdown are all green...The only picture is a large photograph of the well-known little Carpaccio Angel with a lute. We had brought that from Venice last year. There were no ornaments anywhere except a grey and green pot with a lid that [the Rector's wife] had brought me from Damascus; and there were four green candlesticks, two on the dressing table and two on the mantelpiece on either side of the Damascus jar'.

During the Sidgwick's time, the house had no electricity. They relied solely on lamps and candles. Cecily commented,

When we come back in Winter, it takes me a week to get used to that'.

However, whatever internal drawbacks the internal arrangements may have had, the views from the windows over the two acre garden, which was surrounded by trees and contained a number of water features, were superb. Non-locals found the property difficult to locate, as it was not visible from the road and the access drive to it was through a small wood. The fact that a ford had to be traversed added to the sense of remoteness and seclusion. Indeed, the ford could become a raging torrent in winter, rendering the property inaccessible. Cecily commented,

'Although the ford was inconvenient, not to say dangerous, when in spate, it was beautiful, especially by moonlight. It flows across a road for which, after making it, we pay a small yearly rent, and there is a granite footbridge on one side of it with several steps down to the road at each end. we have had to put a hand rail on the bridge, as on dark nights some people found it unsafe that they lay down and wiggled on all fours. The water tears under it over a tumble of granite rocks, amongst which it has made a deep channel, so that if you fell from the bridge in the dark you might easily hurt or even kill yourself. If you fell in the ford, you might or might not come to grief, but you would be up to your middle after much rain'

The Sidgwick's employed two servants - a cook and a housemaid, but after the War, found it almost impossible to find anyone trustworthy, who was willing and able to do such chores for very long. Youngsters now looked for less taxing work and used the new jargon that called domestic servants wage-slaves. Aiming to save costs and overcome some of the difficulties of getting supplies to such a remote spot, the Sidgwicks kept poultry and grew their own vegetables. They played bridge chess with friends and entertained regularly so that one character in the novel commented,

The house seemed to me like a pigeon-cote, with an everlasting flutter of people to and fro... How Thomas and Mary can bear to live where they do I don't understand. They can't telegraph, and their shops are five miles away. The grocer sends once a fortnight, and the butcher refuses to send at all. They get their meat put into a baker's cart, or on the [Boskenna] lorry, and if it comes they are lucky. One day when they were expecting people to dinner, it had not come by tea time and all they could find out by asking here and there was that it had been given to one of the farmers. Luckily the farmer was obliging, and sent it down just in time for the oven. But Mary told me that at Easter their meat had gone quite astray, and had never been traced'.

Creating a garden out of a granite strewn wooded ravine was not a simple task. Furthermore, in addition to the main stream flowing through the lowest level of the garden, there was also a mill leat, which ran through the woods above the house, and this was partially diverted to add additional water features, such as the trout pond. It also overflowed through the property in times of heavy rain, and so this needed to be manged as well.Cecily commented,

'Our lawns were any shape, nearly as rough as a field and divided by a stream garden in which we grew irises, Osmunda, Caltha, Saxifraga Peltata and hundreds of primulas, the kinds that spread and prosper in a wet place'.

There was also a patch crammed with Colchicum, and rows of sweet peas. Howver, they did discover and promote rare plants- Dactylorhiza maculata subsp. ericetorum was registered in the joint names of Alfred and Dick Ullmann (Cecily's nephew) with the Botanical Society of the British Isles in June 1912, whilst Dick Ullmann registered Viola riviana as having been found at Trewoofe in April 1913. She added,

'We never ask people to look at our garden. We know it is not as well kept as it would be if we could spend more on it or work harder in it ourselves. But in our eyes, it is one of the most beautiful gardens we know, because it is made in a wooded ravine and intersected by a deep rushing stream that tumbles over granite rocks, widens near the house into Thomas' trout pond and then hurries to sea again, foamy and gurgling'.

However, in a bad storm, the close presence of woods and stream that gave the garden such character in the summer could become problematic. In the novel, an ash tree falls across the drive, nearly killing them, whilst the trout pool was transformed from a tranquil pond. Cecily wrote,

'It had overflowed its banks in every direction and was tearing over the dam in torrents. All the little streams crossing our garden were swollen too and the main one had spread over the lawns on both sides and was pouring down a bank to the two small ponds given up to plants that flourish in damp places'.

The idea of Alfred having his own trout pond most probably came from John Lamorna Birch, who had created one near his studio by the river lower down the valley. Alfred refused to allow ducks on his pond and whiled away many a happy hour fishing, with his trusty pipe in his mouth. Indeed, when the holidaymakers had gone home and when the servants were in order, it was a beautiful, tranquil spot, and Cecily had a hut constructed on a terrace in the sloping section of the garden at the front of the house where she could do her writing, inspired by the scenery and away from domestic hassles.

The Sidgwicks lived in Trewoofe Orchard for the rest of their lives, with Cecily publishing new novels right up to her death in August 1934, when it was felt that the country had lost a brilliant and valued personality. Alfred, who was reclusive by nature anyway, lived out his final years there quietly, with Ella Naper, whom he had adored, constantly in attendance. He does not appear to have socialised much. In the War years, he was forced to make over rooms for others to stay in. During their time at Trewoofe Orchard Dick and Barbara Waterson received a number of visitors, who recalled Alfred's last few years and painted a picture of a rather grumpy old man, who wanted the child lodging with him to spend all his time out of doors and who locked up the food in the kitchen as he accused the maids of stealing. Maryella Pigott, Ella's niece who stayed at Trewoofe Orchard herself on a number of occasions during the War years, recalls that he was always in his study.

Alfred died in West Cornwall Hospital in Penzance in 22 December 1943, aged 94. He had been in good health until a few weeks before, when he decided, despite his age, to cut down a tree in the garden! The contents of the house were sold at auction in March 1944 but the house itself was then acquired by Cecily's nephew, Dick Ullmann, who let the property for a while but then settled there on his retirement and owned it until March 1959. After the twenty or more years that Dick and Barbara Waterson had lovingly tended and transformed the garden at the property, it has been sold recently and alterations to the house are in progress.

(Article, by David Tovey, in The Flagstaff Issue No 39 Summer 2017).

1. A garden view of Rosemerryn, wisteria in full bloom.

2&3 The Rock Garden at Rosemerrin, by Benjamin Eastlake Leader.

Rosemerrin (aka Rosemerryn)

'Rosemerryn', as it is now known, was originally called 'Rosemerrin' when it was built by Benjamin Eastlake Leader and his wife Bell in 1913. Bengy and Bell had been living in 'Oakhill' since their marriage in September 1910, but had moved out in 1912 when Colonel Paynter decided to modernise the set of three cottages to create a single dwelling for Harold and Laura knight. Presumably as part of this deal, Colonel Paynter agreed to sell Leaders a nearby plot of land upon which they could build their own home. This was in the Trwoofe area of the valley. The access drive to it, which was shared with that of 'Chyangweal', the home that Robert and Eleanor Hughes were building, was some distance along the road to Boleigh, but one boundary of the property adjoined that of 'Trewoofe Orchard', where Cecily and Alfred Sidgwick were also building a new home. Whilst their home was being built, the Leaders lodged at the 'The Reens' - precise location unknown.

'Rosemerrin' was built by Kit Matthews from New Shop on the Land's End Road. It was a large house, constructed of local granite and built in the style of a Cornish Manor, with low beamed ceilings and pitch pine timbers. It also included a large, well-lit studio, which is still in a most impressive space. The whole of the Leader's plot was quite densely wooded and included the Boleigh Fogou (pronounced foogoo)- a rare underground dry-stone structure dating from the Iron Age, which was surrounded by an oval,single-banked ancient fort, whose stone ramparts were still partly in place. However, it was a time when such sites were not so well protected, so that any interesting remains of the interior of the fort appear to have been destroyed in the construction of the house itself, whilst the fort's palisades were removed and the stone used for landscaping in the garden.

Like many of the other new settlers in the valley at this time, Bengy and Bell were keen gardeners and Cecily Sidgwick was clearly most impressed with their efforts, as, in her novels, she frequently has her alter ego, Mary Clarendon, taking quests across from 'Trewoofe Orchard' to see the rock garden in her neighbour's property, and of course, the fogou itself. Bengy seems to have had an interest in botany, as he recorded as registering with the Botanical Society of the British Isles, jointly with Cecily's nephew, Dick Ullmann, Lilium pyrenaicium in JUne 1913, whilst Dick himself registered a viola found at 'Rosemerrin' in July 1914. Bengy's 1915 Royal Academy exhibit was A Corner of My Garden, whilst a number of other rock garden studies by him have also come onto the market.

Sadly, Bengy and Bell had very little time to enjoy their newc home together as, when War broke out in 1914, Bengy enlisted almost immediately and had minimal time with his two children, who were born in June 1914 and June 1916, as he was killed in action in October 1916. The bereft Bell employed a nurse to help with her two very young children, but was helped immeasurably by the Sidgwicks and the Napers. Crosbie Garstin, who came to stay with the Sidgwicks, in the Autumn of 1919, helped Bell to build some stables at the property and she installed a tennis court. Again some of these works seem to have impacted on the archaeological remains.

In c. 1922 Bell decided to move to Bude and 'Rosemerrin ' was rented out on a number of occasions. Hugh Paynter, the brother of Colonel Paynter, rented it for a while in 1922 and it was during this visit that Crosbie Garstin met and fell in love with the niece of Paynter's wife, Lilian Barkworth. When they married in 1924, their first home was 'Rosemerrin', which they rented off Bell, and .although they were forced to move around Lamorna from house to house for the first few years of their marriage, having various spells in 'Rosemerrin', they only acquired it off Bell in 1918...

( Read the complete article, by David Tovey, in Flagstaff Issue No 40 Winter 2017)

THE LAMORNA SOCIETY

THE LAMORNA SOCIETY